PAMANA 2009 SURVEY REPORT

*This webpage contains all of the text, but incomplete graphics from the original article.

You can download the entire document in WORD format here:

Survey Part 1

Survey Part 2.

Survey period: May to August 2009

The results of this survey provides update for the members, will help the council in its strategies and formulate appropriate plans for PAMANA. Among the information gathered was an update of the contact names and cellphone numbers of the members, the current management situation and effectiveness of the MPAs, the people’s organizations and the support from local government. The respondents were also asked about the relevance of PAMANA’s advocacy agenda, their awareness on international and national biodiversity conservation concepts and their views on the link of MPAs to health.

Background

The interviews were conducted in 91% or 111 of 122 member sites by some of PAMANA’s national council officers namely: Fernando Tiburcio and Greg Siaron in Luzon; Eugene Mula/Mario Añabieza and Virgilio Garay in the Visayas; and Benjamin Dellosa and Romulo Villanueva in Mindanao. The member sites not interviewed included those that were logistically too far to be reached, or the peace and order situation was a concern.

The survey was held in May to August 2009 and funded by the Tom Epplett Foundation. The first part of the survey presents the survey results from respondents representing the PAMANA member sites, the second part presents the results from interviews with village or barangay health workers and the third part, the interviews with the catalyst partner.

SURVEY RESULTS

Group 1: PAMANA Members

Communication with members

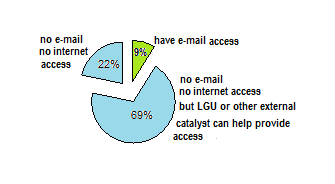

Communication through cellphones appeared to be currently the more practical means to reach the members.

Access to information from members

Majority of the respondents (82% or 91 of 111) were happy to share information about their local MPAs to the public through PAMANA’s website. The other respondents had no response (5% or 6 of 111) or preferred only selected information to be broadcast (13% or 14 of 111). There were 33 of 111 (15 of them had multiple answers) who indicated the selected information they wanted to share were as follows: 1) contact details (n=20); organizational activities (n=20); 3) photos (n=16); 4) monitoring data (n=5); 5) other responses included issues and problems of the sanctuary (n=2), sanctuary regulations (n=1)

Regarding the information the respondents would not like to share, only 5 gave their thoughts (2 of the 5 had multiple answers) as follows: 1) contact details (n=4); 2) photos (n=2); 3) PO activities; 4) monitoring data (n=1); 5) false reports (n=1) and information on non-active members (n=1)

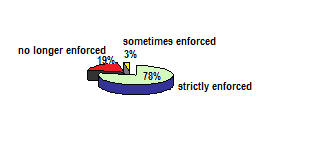

Sanctuary management situationer

The survey results indicated that most of the people’s organizations, i.e. 76% (n=86 of 111) continued to be actively engaged in the management of their marine sanctuaries or MPAs. Only 16% or 18 of 111 mentioned they were no longer active in management of their MPA, while 3% did not give any answer. The organizations hold membership meetings either once a month (31%), once a year (23%), or quarterly (22%). A few (7%) mentioned they meet twice or more per month or that they have not had any meeting during the past year (3%). There were several respondents (15%) who did not provide any answers. In the case of frequency of meetings among leaders of the organizations, the respondents indicated majority held meetings at least once a mo nth (40%) or quarterly (22%). About 7% held their officers’ meeting once every year. However, 5% have not had any meeting at all and 20% provided no answer.

Involvement with MFARMC or PAMB

About 84% (n=93 of 111) said they were members of MPA management councils at the municipal or multi-municipal level, e.g. Municipal Fisheries Aquatic Resource Management Council (MFARMC) or Protected Areas Management Board (PAMB). Thirteen respondents specifically indicated they were MFARMC members while 3 identified their organizations as being represented in the PAMB. One respondent indicated their organization is a member of both MFARMC and PAMB.

Ninety three respondents who were members of the management council, indicated that the management councils held meetings either quarterly (42%) or monthly (34%). The others held meetings only once a year but others frequently met, i.e. twice or more every month (n=4 of 93).

Aside from MFARMC and PAMB, they also attend special meetings called by the DENR, the MLGU or NGOs and fisherfolk alliance assemblies. Such special meetings can occur once a year (n=26 of 78), quarterly (n=22 sa 78), once a month (n=13 sa 78) or more (n=7 sa 78). There were 8 respondents who said no meeting has been called so far in the past year while 2 of 78 said they could not tell exactly how frequent the meeting occurs because it depends on the invitation.

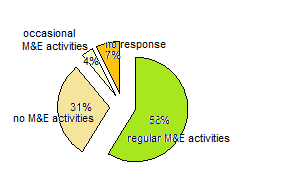

Monitoring and evaluation of the MPAs

Marine sanctuary support

Municipal local government unit (MLGU):

An estimated 65% (n=72 of 111) of the respondents said they received annual financial support for their marine sanctuary. The other respondents did not receive any regular financial support (n=30 of 111) or did not give any answer (n=9 of 111).

Forty-five respondents indicated the amount they receive from Municipal LGUs to help manage their marine sanctuary as follows:

Range: P1,000 to P1,000,000

Median: P10,000

Average: P72,300

However, it is possible that some of the respondents may have given answers that MLGUs provided to many barangay marine sanctuaries within their particular municipality.

The MLGU was identified by 79% or 88 of 111 to provide regular support for their various marine sanctuary activities and another 2% said they received irregular minimal support. Only 8% said they did not receive any support while 11% did not give any answer.

The various kinds of support being provided by MLGUs were as follows:

Barangay Local Government Unit (BLGU):

Thirty four respondents reported receiving annual financial support from the Barangay LGUs as follows

Range: P1,000 to P40,000

Median: P5,000

Average: P8,400

In the case of the BLGU, 81 of 111 respondents said the BLGU currently supports them in their marine sanctuary initiatives while 4 respondents said they were occasionally supported. There were 15 interviewees who responded negatively and 11 who did not provide any answers. The 81 respondents gave the following details on the kind of support provided by the BLGU:

Marine sanctuary management activities

Majority of the respondents indicated they had regular activities related to marine sanctuary management such as holding meetings, patrols, planning and evaluation within the year or have many actions but they were not regularly conducted (i.e. at least 3 meetings, occasional patrols, and communication among members) throughout the year. The rest hardly had any actions (at most only 1 management council meeting) to no actions undertaken in the past year for their sanctuary or managed to conduct only a few activities, e.g. 2 to 3 meetings and 1 to 2 advocacy gatherings in 1 year. Few respondents indicated they were very active in marine sanctuary management, holding regular marine sanctuary activities and that they had broad support from different agencies.

Additional information from respondents on why they were able to implement regular activities or why there were hardly had any actions in the past year were obtained. For those who are able to have regular activities, this was attributed to regular meetings or event of the federation (e.g. Kadagatan festival), there is sustained LGU and NGO support. For those who were unable to conduct regular marine sanctuary management activities, this was because of the inaccessibility of their sanctuary so that support is difficult to reach them, they had no communication or links with the LGU (both municipal and barangay), lack of financial support, patrol or guarding is only voluntary, their organization was weak (reorganization is needed, no replacement for the leader who went on leave), and there is political intervention.

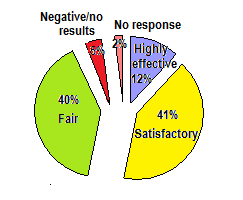

Marine sanctuary effectiveness

Majority of the respondents (41%) perceived their marine sanctuaries to have achieved from 75 to 51% of their expectations while many others indicated only 50 to 26% of their expectations were met (n=40 of 111). Only 13 of 111 perceived their marine sanctuaries have most or all of their expectations were met (i.e., 76% to 100% ). Four respondents said their marine sanctuary had negative results (e.g. fewer fishes now than before) based on their expectations while one said none of the marine sanctuary goals were achieved. Two respondents did not give any response.

Some respondents provided information on why their expectations were not met: 1) weakening of the organization, 2) laxity in guarding the sanctuary, 3) lack of support from the local government LGUs particularly in enforcement, 4) unsustained management activities, and 5) lack of livelihood alternatives. Those whose expectations were met indicated that the success can be attributed to full support of volunteer fish wardens (bantay dagat) and the effective information campaign in neighboring barangays.

Relevance of PAMANA’s advocacy agenda

About 40% or 45 of 111 respondents said all five PAMANA advocacy agenda are still relevant. Some mentioned only 3-4 of the 5 are relevant (24 of 111) while 16 of 111 believed only 1 to 2 are relevant although 3 of these 16 respondents admitted they had no knowledge about the PAMANA advocacy agenda. A few (n=9 of 111) indicated more agenda should be included such as supplemental livelihoods, sustained financial support, tourism (cottages or resthouse facilities for visitors). Seven respondents had no answer.

Other responses that respondents believed PAMANA should provide support included providing facilities such as patrol boats and marker buoys, reorganization of people’s organizations, information campaign in neighboring islands, and help address local issues/concerns.

Linkaging among PAMANA chapter members

Almost half of the respondents (43% or 48 of 111) said they have no communication or links with other PAMANA chapter members while 41 of 111 said they are able to communicate once or twice a year. Very few (n=12 of 111) indicated they meet or communicate with other PAMANA members frequently, either every month (n= 12 of 111) or through cellphones weekly (n=2 of 111). Only 1 said they keep in touch everyday. Seven respondents had no answer.

Some respondents gave information on why they had not been linking with other PAMANA members: financial limitations, no meetings organized, no NGO in the area, the PAMANA representative officer has resigned, no information updates and broken cellphones. Those who communicate with each other frequently were facilitated by the LGU or NGO who sponsors meetings within their municipality or chapter.

PAMANA membership needs

The respondents gave suggestions on how the members can be served as follows:

Suggested activities |

count |

conduct trainings, seminars |

30 |

conduct Information, education campaigns (IEC), including updating the members on new management strategies,opportunities, etc. through internet, cellphone, reading materials |

23 |

promote advocacy of small fisherfolk (marine court, institutionalization of fish warden, etc) |

20 |

provide livelihood programs |

18 |

conduct meetings, conferences |

14 |

provide proposal making, fund sourcing skills |

14 |

launch programs to improve marine sanctuary mgt (incl new mgt strategies, etc) |

10 |

documentation, monitoring |

5 |

networking, linkaging |

5 |

provide logistical needs of marine sanctuaries, e.g. materials, markers |

5 |

provide regular updates |

3 |

sustain initiatives; unspecified, general |

3 |

assist in technical aspect |

3 |

empowerment, organizing, PO strengthening |

3 |

assist in making marine sanctuaries functional again |

3 |

conduct PAMANA council meeting |

2 |

raise funds (so meetings and activities can be conducted, implemented) |

1 |

scholarship for children for fishers |

1 |

Note: 55 of 111 respondents had multiple responses; 16 of 111 did not provide any answer

A few more insights, comments and suggestions provided by some respondents for the PAMANA secretariat to consider were the following:

Expressed the desire for PAMANA to continue its campaign to care for our seas with everyone helping each other; that PAMANA will have a general assembly and PAMANA can sustain its activities and achieve its plans, source its funds to continue the advocacy |

6 |

Hoped that PAMANA can provide facilities for the local areas including cell phones, patrol boats, telescopes, reflectorized buoys; also that it can extend assistance in monitoring the marine sanctuaries and facilitate communication among members |

5 |

When PAMANA is revived, they indicated the need for PAMANA to provide some assistance at the local chapters, making plans at the local level based on the needs of each member site at the local level towards a more successful management of the marine sanctuaries |

5 |

That any agreements or proposal entered into by PAMANA particularly with international organizations with marine thrust should be fed back to members for awareness and to help the grassroots in terms of advocacy for marine conservation management, and the agenda of PAMANA and also include climate change issues and concerns |

4 |

Hoped that the management approaches to their sanctuary will be changed to a more appropriate one; that when there are new and relevant policies or laws gathered by the PAMANA secretariat, these should be impartedto members, e.g. the marine bioregions. Frequent updates on PAMANA’s programs will be ideal; and that these programs will support the marine sanctuary management of each local area |

3 |

PAMANA should facilitate the dissemination of the success of the marine sanctuaries in each municipality so that other people will be aware and understand and appreciate the effect of the marine sanctuaries and give their support |

2 |

Provide guidance on how to address requests for joining PAMANA and those who want assistance in establishing a sanctuary |

2 |

PAMANA’s assistance on fund sourcing for the development of their marine sanctuaries; livelihoods for people’s organizations and project proposal development for all PAMANA member sites. |

2 |

Address the concern on where to place additional growing chapter members specially when they belong to different municipalities. |

1 |

Connecting with international movements

Majority of the respondents stated they were aware of the marine biodiversity conservation concept (55% or 61 of 111) while 23% or 26 of 111 indicated they have no knowledge of this concept and 22% or 24 of 111 failed to give any response. For those who responded on the affirmative, 61 provided some information on what they perceived the marine biodiversity conservation concept as follows:

The variation of living things, particularly the marine resources are important |

28 |

Caring for the marine resources/marine environment |

10 |

Marine sanctuaries are part of the marine ecosystem and is therefore part of marine biodiversity conservation |

9 |

rehabilitation/restoration of degraded coastal/marine resources |

7 |

The connectedness of every creature in the sea |

6 |

Lacks knowledge |

2 |

This concept is necessary to ensure the productivity of the ecosystem |

2 |

Promote new technologies on fish farming/fish productivity |

1 |

Endangered species of marine biodiversity |

1 |

The concern on biodiversity conservation is also perceived by 78% (n=87 of 111) of the respondents as important. Only 2 respondents thought this was not an important concern and 20 did not give any answer. For those who thought marine biodiversity conservation was important the following were the reasons provided:

Provides information and knowledge among citizens |

35 |

Helps society |

22 |

Preserves our seas and enlighten people on the significance of the marine resources |

12 |

Helps preserve the balance of our ecosystem |

10 |

Helps address the problems on global warming or climate change |

2 |

Source of food security |

2 |

Increases awareness on the need to control human population |

1 |

Majority of the respondents said they did not have any knowledge of the six marine bioregions of the Philippines (n=72 of 111) while 31 did not provide any answers. Only 8 of 111 said they have heard of the six marine bioregions. However, of these 8 respondents, only 4 provided answers on which marine bioregion they belong to. Of these 4, only 1 got this correctly.

Marine Sanctuaries and Health

A total of 107 of 111 respondents or 96% indicated their marine sanctuaries help address the health and nutrition needs of their village or barangay. Only 1 did not think marine sanctuaries and health had no connection and 3 respondents did not give any answer.

Those who said marine sanctuaries are important to health gave information on why this was important to health as follows (37 interviewees gave multiple answers):

more fishes/abundance of fishes |

47 |

Provide food and nutrition |

38 |

Catch increases |

23 |

source of protein |

14 |

Link to income, livelihood therefore can buy more food |

13 |

Helps keep coast clean and free from pollution |

8 |

environmental awareness |

7 |

Provide food to the children |

3 |

Majority of the respondents (n=102 of 111) believed that the designated village or barangay health workers (BHW) can help promote the link between marine sanctuaries and good health and nutrition. Only 1 did not think BHWs can promote this link while 8 of 111 did not give any answers.

Group 2: Village or Barangay Health Workers (BHW) as respondents

The general profile of the BHWs were obtained from the responses which showed at least 96 of 111 appeared to be females based on their first names and 2 have obvious male first names. Thirteen of 111 interviewees gave no response. Majority of the respondents (n=28) had 6 to 10 years experience while 22 had 1 to 5 years experience. The rest had more than 10 years experience (n=46).

All respondents (100 of 111) who gave an answer said the marine sanctuaries can help address health and nutrition problems in their coastal barangay. BHWs from 11 marine sanctuary member sites did not give any answer. The respondents also ranked the importance of the marine sanctuaries to good health and nutrition as follows:

Not important - 0

Not very important - 1% o 1

Important – 43% o 48 sa 111

Very important – 44% o 49 sa 111

Critically important - 0

No response : 12% o 13 sa 111

Most of the respondents also indicated that they involve themselves (n=91 of 111) in some marine sanctuary management activities (e.g. coastal clean up, patrolling) while 15 of 111 said they were not involved in any marine sanctuary management activities. Four other respondents did not give any response.

Group 3: Catalysts as the respondents

The respondents came from either the office of the municipal mayor (n=42), the municipal agriculture’s office (n=19), the non-government organization (n=10) and the academe (n=2). Catalyst partner agencies of 38 member sites were not interviewed.

The programs that the catalyst agencies implement were provided by 71 respondents where 49 of them gave multiple or more than one answer as follows:

Program/s |

Count |

Through annual budget support ; allocating funds |

73 |

Monitoring sa corals ug isda and evaluation |

19 |

Strengthening of people’s organization, trainings, capacity building |

15 |

conduct seaborne patrolling; enforcement |

13 |

Logistics support |

12 |

Law enforcement; legal support |

10 |

Technical support |

9 |

Facilities support |

8 |

Making plans |

7 |

Information and education campaign |

7 |

Coordination with BFAR and NGO; linkaging, networking |

6 |

Moral support |

3 |

Insurance benefits (accident insurance through Philhealth) |

3 |

Livelihood projects |

2 |

general support |

1 |

Advocacy |

1 |

Implementing coastal resource management program in the locality |

1 |

The catalyst partner interviewees indicated they hold regular meetings with the people’s organization and the community managing their marine sanctuaries (n=53). Eleven mentioned they did not have regular meetings with the community managers although 2 said they used to conduct meetings before.

The frequency of site visits made by the catalyst partner were quarterly (n=23), once a month (n=20), once a year (n=8) or more than twice a month (n=3). Three respondents said they did not hold any meeting in the past year.

Majority of the catalyst partner agencies were willing to be the messengers for PAMANA members through e-mail (n=59 of 111) and very few (n=2 of 111) could not do so while 50 of 111 did not give any answer.